Nonperforming loans (“NPLs”) refer to those financial assets from which banks no

longer receive interest and/or installment payments as scheduled. They are known as

non-performing because the loan ceases to “perform” or generate income for the bank.

Choudhury et al. (2002: 21-54) state that the nonperforming loan is not a “uniclass”

but rather a “multiclass” concept, which means that NPLs can be classified into

different varieties usually based on the “length of overdue” of the said loans.

NPLs

are viewed as a typical byproduct of financial crisis: they are not a main product of

the lending function but rather an accidental occurrence of the lending process, one

that has enormous potential to deepen the severity and duration of financial crisis and

to complicate macro economic management (Woo, 2000: 2).

This is because NPLs

can bring down investors’ confidence in the banking system, piling up unproductive

economic resources even though depreciations are taken care of, and impeding the

resource allocation process.

In a bank-centered financial system, NPLs can further thwart economic recovery

by shrinking operating margin and eroding the capital base of the banks to advance new

loans. This is sometimes referred to as “credit crunch” (Bernanke et al., 1991: 204-248).

In addition, NPLs, if created by the borrowers willingly and left unresolved, might act

as a contagious financial malaise by driving good borrowers out of the financial market.1

Further, Muniappan (2002: 25-26) argues that a bank with high level of NPLs is forced

to incur carrying costs on non-income yielding assets that not only strike at profitability

but also at the capital adequacy of a bank, and in consequence, the bank faces difficulties

in augmenting capital resources.

Bonin and Huang (2001: 197-214) also state that the

probability of banking crises increases if financial risk is not eliminated quickly. Such

crises not only lower living standards but can also eliminate many of the achievements

of economic reform overnight.

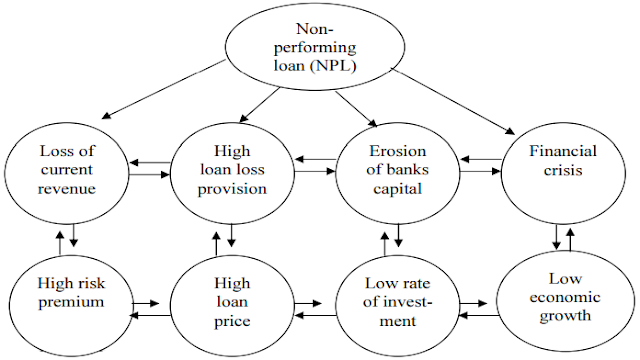

The economic and financial implications of NPLs in a

bank-centered financial economy can be best explained by the following diagram:

The above figure illustrates the catastrophic effect of NPLs in a bank-centered Fig. 1 Economic and financial implications of NPLs

financial system. Having such a system, Bangladesh needs to study the condition of

NPLs on a routine basis in order to augment investible capital in the productive sectors

as well as to ensure sustainable economic growth.

It can be said unequivocally that NPLs are the result of economic slowdown. For

instance, Cargill et al. (2004: 125-147), Barseghyan (2003: 12), Fukui (2003), Shiozaki

(2002: 27), Hoshino (2002: 3-19), Takeuchi (2001: 37-38) have identified Japan’s high

level of NPLs as an outcome of prolonged economic stagnation and deflation in the

economy since the bursting of the “bubble” in the early 1990s.

In addition, Hanazaki

et. al. (2002: 305-325) and Yanagisawa (2001: 2-9) highlight cross-shareholdings, stock

market volatility, virtual blanket guarantee of bank debts and the system of “relationship

banking”2

as factors responsible for the prolonged fragility of the Japanese banking sector.

According to the definition of the Financial Reconstruction Law (FRL), the total

amount of NPLs of all banks in Japan as of the end of March 2003 was 35.3 trillion yen,

although there are claims that the actual amount of NPLs might exceed 100 trillion yen.

On the other hand, the causes of the financial and exchange rate crisis that erupted in

East Asia (Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia and Indonesia) in 1997 are viewed as high shortterm external debts, excessive loans for real estate, large current account deposits, high

international interest rates and weaknesses in the balance sheet of financial institutions.

In addition, Kwack (2000: 195-206) finds that the 3-month LIBOR interest rate and

nonperforming loan rates of banks were the major determinants of the Asian financial

crisis. Huang and Yang (1998: 11) report that unlike the other countries of East Asia,

China did not face financial fragility because of the size of its foreign exchange reserve,

its current account surplus, the dominance of foreign direct investment in capital flows

and the control of the capital account.

As of June 2003, China recorded only 5.68% of

its total loans as nonperforming while, in contrast, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines and

Malaysia record NPLs at 15.29%, 8%, 15% and 8.7% respectively. Unfortunately, the

present (December, 2005) rate of NPLs in China has increased to 8.6%.

In the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal),

however, the causes of nonperforming loans are usually attributed to the lack of effective

monitoring and supervision on the part of banks (as required by the BASEL principles

of bank monitoring and supervisions), lack of effective lenders’ recourse, weaknesses of

legal infrastructure, and lack of effective debt recovery strategies.

Among the countries

in the Indian sub-continent, the rate of NPLs as a percentage of total loans disbursed in

2005 is seen to be minimal in India (5.2%), followed by Sri Lanka (9.6%). Bangladesh,

however, still records a staggering rate of 13.56%.

The issue of nonperforming loans in Bangladesh is not a new phenomenon. In

fact, the seeds were cultivated during the early stage of the liberation period (1972-1981),

by the government’s “expansion of credit” policies on the one hand and a feeble and

infirm banking infrastructure combined with an unskilled work force on the other (Islam

et al., 1999: 35-37).

Moral et al. (2000: 13-27) argue that the expansion of credit policy

during the early stage of liberation, which was directed to disbursement of credit on

relatively easier terms, did actually expand credit in the economy on nominal terms.

However, it also generated a large number of willful defaulters in the background who,

later on, diminished the financial health of banks through the “sick industry syndrome”.

Islam et al. (1999: 22-31) add that despite the liberalizing and privatizing of the

banking sectors in the 1980s with a view to increasing efficiency and competition, the

robustness of the credit environment deteriorated further because of the lack of effective

lenders’ recourse on borrowers.

Choudhury et al. (1999: 57) find that Government

direction towards nationalized commercial banks to lend to unprofitable state owned

enterprises, limited policy guidelines (banks were allowed to classify their assets at their

own judgments) regarding “loan classification and provisioning” , and the use of accrual

policies of accounting for recording interest income of NPLs resulted in malignment of

the credit discipline of the country till the end of 1989.

In the 1990s, however, a broad based financial measure was undertaken in

the name of FSRP5

, enlisting the help of World Bank to restore financial discipline to

the country. Since then, the banking sector has adopted “prudential norms” for loan

classification and provisioning.

Other laws, regulations and instruments such as loan

ledger account, lending risk analysis manual, performance planning system, interest

rate deregulation, the Money Loan Court Act 1990 have also been enacted to promote

sound, robust and resilient banking practice.

Surprisingly, even after so many measures,

the banking system of Bangladesh is yet to free itself from the grip of the NPL

debacle. The question thus arises, what are the reasons behind such a large proportion

of nonperforming loans in the economy of Bangladesh?

Is it because of “flexibility

in defining NPLs” or lack of effective “recovery strategies” on the part of the banks?

Alternatively, is it due to poor enforcement status of laws related to nonperforming

loans? The present study has concentrated on the above issues mainly with a view to

assisting policymakers to formulate concrete measures regarding sound management of

NPLs in Bangladesh.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 deals with the current loan

classification and provisioning system in use in Bangladesh with a view to

understanding the country’s system of classification of NPLs as compared to the

international standard.

Section 3 traverses the different varieties of NPLs (substandard,

doubtful and bad). Section 4 discusses the enforcement status of laws relating to default

loans in Bangladesh. It needs to be mentioned that in a bank-centered financial system,

the central bank plays an important role in the governance of banks.

Therefore, an

attempt is made in section 5 to understand the measures undertaken by the central bank

in relation to the management of NPLs in Bangladesh. Section 6 provides a summary of

the findings and the major challenges to addressing the NPL problem, while concluding

remarks are given in section 7 of this paper.

Posting Komentar untuk "Nonperforming Loans in the Banking Sector of Bangladesh"