The social health insurance model

Funding access to health care through social health insurance has its origins in Germany in the nineteenth century. The earliest versions of health insurance developed without any significant government intervention.

Industrialization brought with it the emergence of large firms, and the workers in these firms started to organize themselves into trade unions.

Sickness funds organized by the workers for mutual support often attracted support from employers, who saw benefits in their workers having access to better health care.

Thus, a model arose in which health insurance was provided for some or all the workers in a firm, with much of the control remaining with the workers but with some management and financial input from employers.

The early sickness funds varied in their structures and governance but were mainly based on mutual support (in which contributions were based on income) and provided access to care based on need. In Germany, under Chancellor Bismarck, the sickness funds were formalized into a broader and more consistent system of health insurance.

This led to the eventual development of territorial funds, which provided health insurance for those who were unable to obtain benefits through large formal employers (Altenstetter 1999; Busse 2000). The current arrangements in Germany have evolved slowly and in response to problems that emerged.

In addition, traditions and unwritten rules have a strong role in the German system. These are just as important as the formal rules. It has continued to use the language and traditions of insurance, despite formal similarities to systems of government financing of care.

It has also given priority to allowing choice of provider. This chapter is organized into five sections. The first outlines the key features of social health insurance and how it operates. The second considers the variation in social health insurance in western Europe, in particular in France, Germany and the Netherlands.

The third section analyses recent reforms in western Europe and considers to what extent they have met their objectives.

The fourth section evaluates social health insurance and presents its strengths and weaknesses, and the final part draws conclusions about the lessons from western European experience for the development of social health insurance in other countries.

There is substantial literature on the structures, operation and various technical aspects of social health insurance (Roemer 1969; Ron et al. 1990; Normand and Weber 1994). In this section, we outline the key features of social health insurance and how it operates.

Social health insurance has no uniformly valid definition, but two characteristics are crucial. Insured people pay a regular, usually wage-based contribution. Independent quasi-public bodies (usually called sickness funds) act as the major managing bodies of the system and as payers for health care.

These two basic characteristics have certain limitations. In France’s mutual benefit associations, contributions are based on income and usually split between employers and employees – but insurance is entirely voluntary (also called private social health insurance).

A part of Switzerland’s compulsory health insurance is not run by sickness funds but by privately owned insurance companies.

We therefore use a pragmatic definition that also leaves room for innovative approaches: social health insurance funding occurs when it is legally mandatory to obtain health insurance with a designated (statutory) third-party payer through contributions or premiums not related to risk that are kept separate from other legally mandated taxes or contributions.

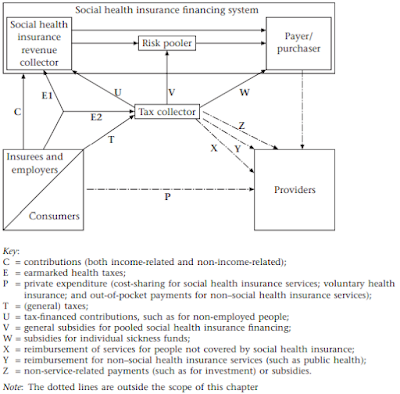

In Figure 3.1, these two characteristics relate to the arrow C and the box ‘payer/purchaser’.2 Several other characteristics are frequently found in social health insurance funding and fund management, although they are not essential features of the model.

1 Social health insurance is compulsory for the majority or for the whole population

Early forms of social health insurance normally focused on employees of large firms in urban areas. Over time, coverage has expanded to include small firms and, recently, self-employed people and farmers. It is today typically compulsory for most or all people, although some countries exclude people on high incomes from social health insurance (such as the Netherlands) or allow them to opt instead for private insurance (such as Germany).

2 There are several funds, with or without choice and with or without risk-pooling

Some countries have more than one sickness fund but little choice, since people are assigned to funds based on their geographical location, occupation or both.

In others, there is a choice among funds, which stimulates competition but may also bring potential difficulties in ensuring equal access to care for all.

Four broad types of organization of sickness funds can therefore be differentiated: a single fund for the entire population of a country; single funds serving geographically distinct populations within a country; multiple funds serving the population in the same geographical area but that do not compete for insurees; and multiple competing funds.

Where there is more than one (competing or non-competing) fund, risk-pooling should ensure that funds with low-cost and/or high-income members subsidize those with high-cost and/or low-income members. However, this is politically and technically difficult.

Posting Komentar untuk "The social health insurance model"